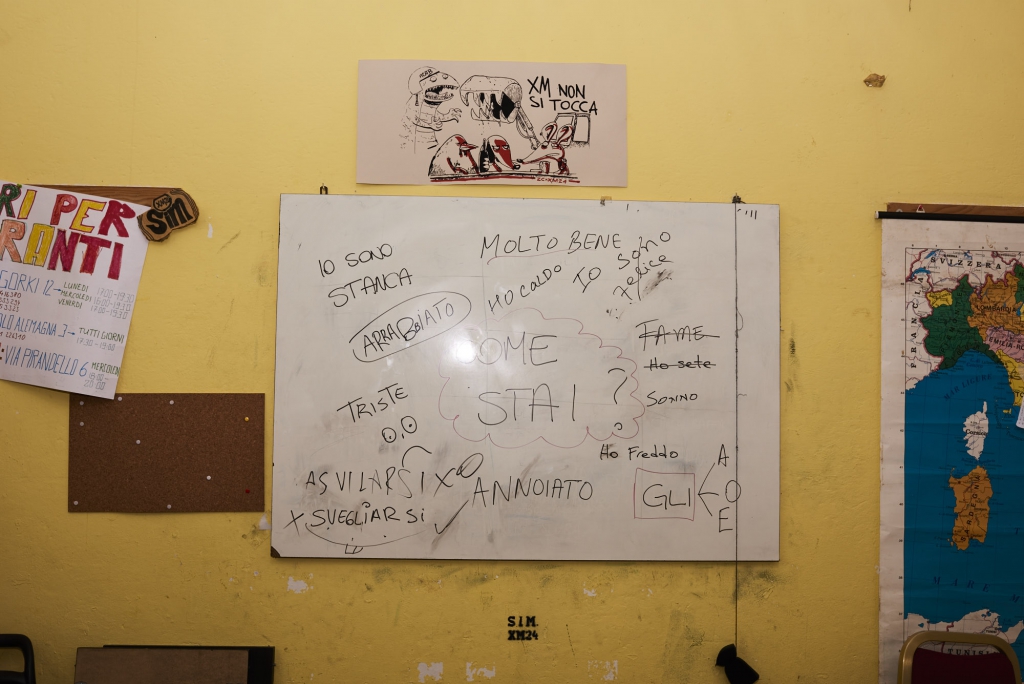

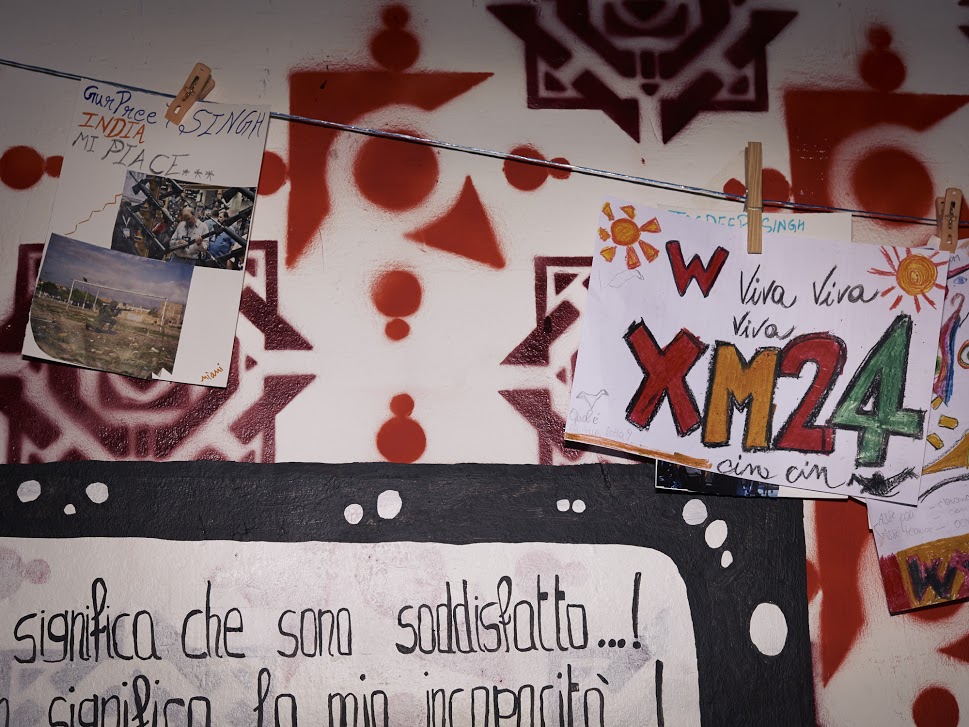

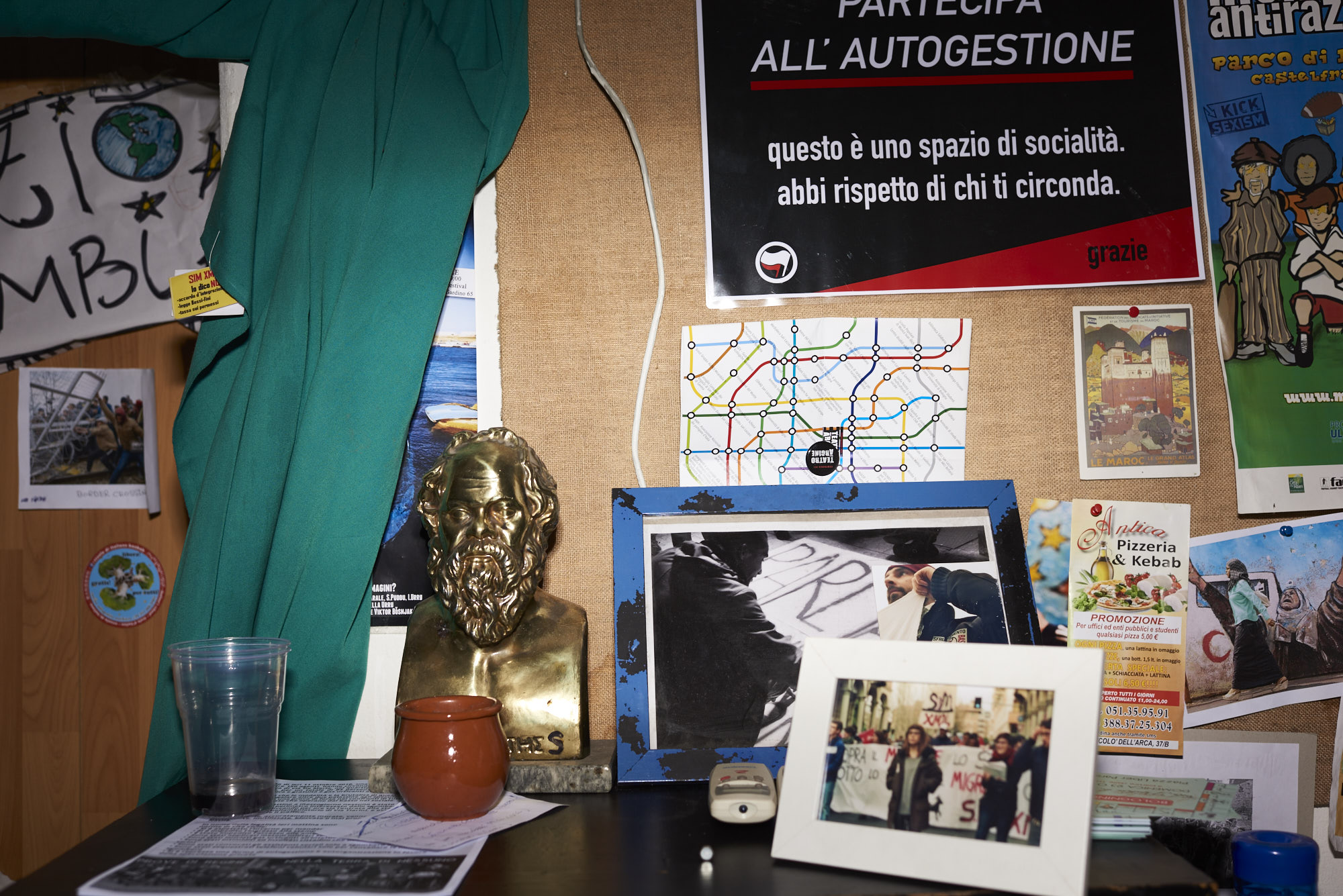

Hidden behind the graffiti and street-art walls of an abandoned warehouse in northern Italy, migrants gather in a classroom to learn Italian. This is Scuola di Italiano migranti – the Italian school for migrants.

“This place is beautiful. I learned Italian here. I have a lot of friends here. It’s like a big family,” Salman tells us. He moved to Bologna from Pakistan 10 years ago.

“I’ve seen a lot of things in my life, beautiful but also difficult things. But this school is the best place to experience life,” he explains.

“Here people are anti-fascist, anti-capitalist and anti-racist. They make no money. Here you can learn about other cultures.”

“This school is like a home to me. All the others asked me for documents, but here I didn’t need any,” says Youssef, from Morocco.

“When I was looking for a school to learn Italian, I came here,” adds Alejandro, who arrived from Mexico. “I’ve learned a lot here. The teachers make an effort to give us everything so that we can learn to speak Italian.”

The school is run by a left-wing squat known as XM24. Members are politically active and often hold debates and meetings, as well as running a self-funding bar and medical centre. Lessons are taught by volunteers, mainly university students and young workers.

“It’s not a service offered to migrants. We all want to be part of the same shared experience,” explains Sara, one of the teachers.

This school is like a home to me. All the others asked me for documents, but here I didn’t need any.

“We discuss everyday life, from society and housing to racism and sexism. It really is an exchange – not simply us as ‘Italian teachers’ teaching Italian.”

“It’s a school for migrants, yes, but migrants don’t come here to receive anything from us. We want to live the experience with them,” says Laura.

“The student learning Italian is usually taught or put in a position of inferiority,” adds Anna.

“The idea of this school is that we go one step further. People are people. Of course, language barriers can be a problem but we aim not to be superior. We build the lesson together. The student feels more valued.”

It is this approach to teaching that allows migrants to talk openly about their struggles in Italy. Many of them are not allowed to work without a residence permit, but nobody will give them a place to live without a job.

“There are no more jobs for us. We’re all being replaced by robots. Ten years ago Europe wanted people for manual jobs. Not any more – now they want us to leave,” explains Salman.

I’ve seen a lot of things in my life, beautiful but also difficult things. This school is the best place to experience life.

Mehdi, who is also from Morocco, adds: “Times have changed. In the 1990s, factories were actively going out and looking for people to work for them. There were jobs. Not any more. The laws have changed. The law doesn’t help us.”

“I’ve been in Italy for 10 months now,” says Youssef. “For a lot of Moroccans, Europe is seen as a dream, a paradise, but it isn’t. I tell people back home that it’s not a paradise, but they don’t believe me.”

The school also lives under constant threat of closure. The council wants to sell off the land to regenerate the area. Without any legal status, the school could close down tomorrow. “They want to shut this place down. What would you do? Where do you go?” Salman asks.

For now, though, Mehdi says the school is helping to break down the barriers that exist in society: “If you have good thoughts, you know how to treat people. If you have bad and old thoughts, you hate. There are good people who have travelled and who understand cultures.”

Anna tries to explain: “To start with it was difficult to understand, but the more you take part, the more you understand. Now it’s part of my life.

“This school is important for me. It helps to break down the social structures that suffocate freedom of expression. At school we were taught to be afraid of making mistakes. Here you go beyond that.”

Pictures were taken by James Whitty. The names above have been changed.

Leave a Reply